In the middle of writing this column, I received an email titled “4 Benefits That Make College Affordable.” This generic title masked the true purpose of the email — advertising the financial benefits of joining the U.S. Army. To summarize one of my favorite memes in a way that’s appropriate for this publication — sorry, but I’m not dying for an oil company.

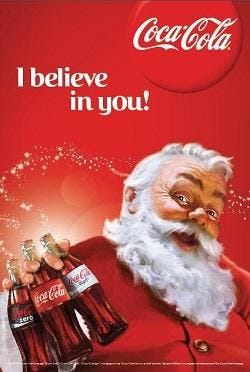

We’re bombarded with as many as 5,000 advertisements each day, a 900% increase from the 1970s. It’s exhausting to be on the receiving end of this seemingly infinite stream of commercials, sponsorships and promoted posts encouraging us to do anything from drink Coke to enlist in the military. Worst of all, there’s little that consumers can do to take back their power.

The modern world necessitates being plugged into social media, checking your email and reading the news — all minefields of increasingly frequent and personally tailored advertisements. It’s hard to envision a way to reverse the universality of marketing, at least as long as we’d like to continue using Twitter and YouTube for free.

But if nothing else, consumers can always vote with their wallets. We need to learn to reward good advertisements by purchasing that company’s product, but more importantly punish bad advertisements by doing the opposite. In other words, we need to become more critical consumers, able to define “good” and “bad” beyond what makes us feel the most comfortable or related to.

A good advertisement is, above all, about the merit of a product or service. It may use a catchy jingle or a perfectly focus-grouped logo, but its main goal isn’t to subconsciously manipulate you or hide its intentions. Rather, it’s a relatively objective presentation of the value and utility of a good.

In its most basic form this means clearly conveying honest information — something like a picture of the product, its price and perhaps a fact or two about it. It should give consumers the information they need to make an informed purchasing decision. A bad advertisement is, well, probably most of what we see every single day.

The most recent Coke Christmas commercial is an exemplar of this manipulative and insubstantial nonsense. It tells the heartwarming tale of a man’s journey to deliver his daughter’s letter to Santa. After braving a shipwreck, scaling a cliffside and trekking through a frigid arctic landscape the poor guy finally gets to the North Pole just to find out it’s too late — Santa has already left to deliver presents. Upon opening the letter, he finds out that she just wanted Santa to “bring daddy home for Christmas” all along. His daughter’s wish won’t be coming true, or so he thought.

Out of the blue, a Coca Cola truck arrives to deliver the devoted family man to his daughter, fulfilling her Christmas wishes. And with this conclusion, viewers now correlate the product with good times and family values. The product itself was never directly advertised. The man doesn’t describe the delicious taste of Coke or some improvement in the product. Rather, the corporation has bypassed all of that in favor of manipulating the consumer into associating Coke with comforting emotions.

This may be an extreme example, but we see ads like this constantly. A less tactful version of this exploitative strategy is seen in the recent flurry of Grubhub commercials, which feature an obnoxiously catchy flute riff and the message that using their service will bind together your dysfunctional family.

An even more nefarious type of manipulative marketing seeks to clean up and humanize a company’s image, usually in response to some sort of criticism over unethical business practices or weak response to the COVID-19 pandemic. If I had a dollar for every time a megacorporation reminded me that “we’re all in this together” or “our workers are heroes,” I’d have been able to Grubhub every meal since last April.

Of course, when companies like Walmart and Amazon fawn over their employees in commercials — referring to them as frontline heroes who are selflessly serving the public during these trying times — it’s rarely backed up by action. Amazon ran an ad in May titled “Thank You Amazon Heroes” that was notably devoid of any concrete action that the company is taking to thank these workers. Amazon now claims to be taking the utmost safety precautions, but employees have repeatedly told a different tale, even after this ad was released.

The politics of labor exploitation aside, these ads make no effort to promote the merit of some product or service. Rather, they seek to create sympathetic feelings for an inanimate good. Companies like Amazon want consumers to conflate their uplifting messaging with the quality of their service — a strategy that’s been leaned on particularly hard during the pandemic.

I don’t think that corporations are entitled to our hard earned dollars just because they have a blank check advertising budget and a wealth of data on the consumer psyche. By becoming critical consumers and remembering the “why” behind a purchase, we can regain a bit of autonomy in a world of omnipresent marketing.